The mind has a peculiar connection with repetition. Consider the phenomenon of déjà vu, where we mistakenly feel we’ve encountered a new situation before, giving rise to an eerie sensation of familiarity.

However, our findings reveal that déjà vu serves as a glimpse into the functioning of our memory system.

According to our study, the occurrence of déjà vu stems from a desynchronization between the brain’s familiarity detection and reality. Déjà vu serves as a signal highlighting this peculiarity, functioning as a form of “fact-checking” for the memory system.

However, the act of repetition can lead to something even more eerie and exceptional.

Contrary to déjà vu, “jamais vu” occurs when something familiar feels unreal or new. In our recent study, honored with an Ig Nobel award for literature, we delved into the mechanics of this phenomenon.

Jamais vu can manifest as perceiving a familiar face and suddenly finding it unfamiliar or unknown. Even musicians experience it fleetingly, momentarily losing their way in a well-known musical passage. It can also occur when visiting a familiar place, leading to disorientation or seeing it with a “fresh perspective.”

This phenomenon, even rarer than déjà vu, proves to be perhaps even more unusual and disconcerting. When individuals are asked to recount it in daily life experience surveys, they describe instances such as: “While writing exams, I correctly write a word like ‘appetite,’ but I repeatedly glance at it, plagued by second thoughts that it might be incorrect.”

In everyday life, this experience may be triggered by repetition or prolonged staring, but it doesn’t have to be. One of us, Akira, encountered it while driving on the motorway, leading him to pull over onto the hard shoulder to reset his unfamiliarity with the pedals and steering wheel. Fortunately, such occurrences are rare in the natural environment.

Simple set up

Our understanding of jamais vu is limited, but we hypothesized that inducing it in a laboratory setting would be relatively straightforward. Merely instructing someone to repeat a task or phrase often results in it losing meaning and becoming perplexing.

This constituted the fundamental structure of our jamais vu experiments. In the initial study, 94 college students were tasked with repetitively writing a single word. They performed this task with twelve distinct words, spanning from common ones like “door” to less familiar ones like “sward.”

We instructed participants to swiftly replicate the given word, emphasizing they had the option to stop. Various reasons were provided for halting, including experiencing an unusual sensation, boredom, or discomfort in their hand.

The most frequently chosen reason for stopping was the sensation of things becoming peculiar, selected by approximately 70% of participants, indicating an experience we defined as jamais vu. This commonly occurred after around one minute (33 repetitions), typically with familiar words.

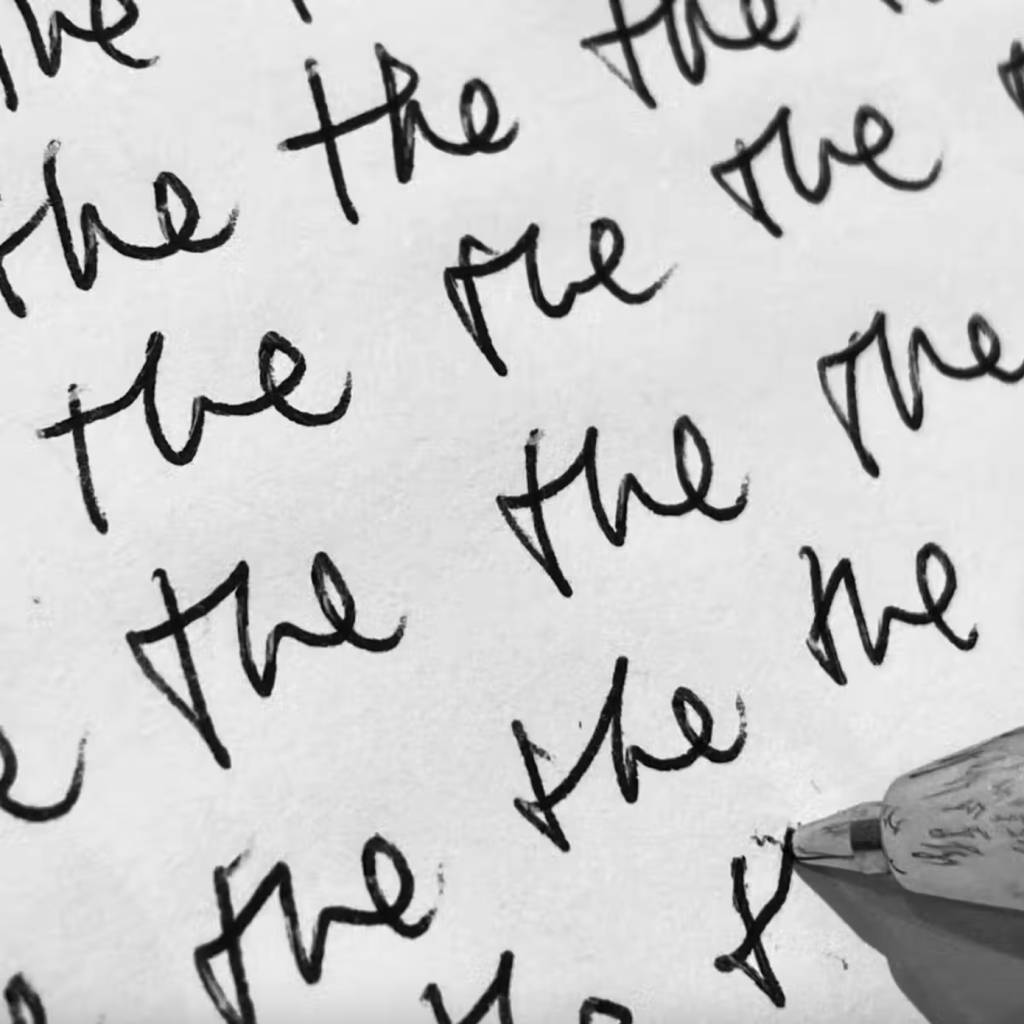

In a subsequent experiment, we exclusively employed the word “the,” considering its ubiquity. In this instance, 55% of individuals ceased writing, citing reasons aligning with our definition of jamais vu (but after 27 repetitions).

Participants articulated a spectrum of experiences, spanning from “They lose their meaning the more you look at them” to “seemed to lose control of hand,” with our favorite being, “it doesn’t seem right, almost looks like it’s not really a word but someone’s tricked me into thinking it is.”

It took approximately 15 years to compile and publish this scientific research. In 2003, we followed an intuition that individuals would experience a peculiar sensation while repetitively writing a word. Chris, one of us, had observed that the lines he was instructed to repeatedly write as a disciplinary measure in secondary school made him feel peculiar – as if reality were altered.

The 15-year duration was a result of our realization that the phenomenon wasn’t as novel as initially perceived; we weren’t as clever as we thought. In 1907, one of psychology’s often overlooked pioneers, Margaret Floy Washburn, conducted an experiment with a student, revealing the “loss of associative power” in words stared at for three minutes. Over time, the words became strange, lost their meaning, and fragmented.

We essentially rediscovered a well-established concept. Introspective methods and inquiries of this nature had merely fallen out of favor in the field of psychology.

Deeper insights

Our distinctive contribution lies in the proposition that the shifts and diminishments of meaning during repetition are accompanied by a distinct sensation – jamais vu.

Jamais vu serves as a signal that indicates when something has grown excessively automatic, too fluent, or overly repetitive. It assists us in “snapping out” of our current processing, and the sensation of unreality functions as a reality check.

Logically, such occurrences take place. Our cognitive systems need to maintain flexibility, enabling us to shift our attention to wherever it’s required instead of becoming engrossed in repetitive tasks for extended periods.

Our comprehension of jamais vu is still in its infancy. The predominant scientific explanation revolves around “satiation” – the saturation of a representation to the point where it becomes nonsensical.

Connected concepts include the “verbal transformation effect”, where the repetition of a word activates neighboring associations. Thus, while initially hearing the repeated word “tress,” listeners may later report perceiving “dress,” “stress,” or “florist.”

There also appears to be a connection with research on obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), which explored the impact of compulsively fixating on objects, such as illuminated gas rings. Similar to repetitive writing, these effects can induce a strange sensation, causing a slip in reality. This correlation might aid in our understanding and treatment of OCD.

Continuously verifying if the door is locked, to the point where the task loses its significance, can create a challenge in determining the actual locked status. This initiates a detrimental cycle, making it difficult to break the loop of uncertainty.

In the end, we are honored to receive the Ig Nobel Prize for Literature. The recipients of these awards produce scientific works that “make you laugh and then make you think.”

We aspire that our exploration of jamais vu will serve as inspiration for further research, leading to even more profound insights in the foreseeable future.

This post has been reissued from The Conversation under the terms of a Creative Commons license.

A prior edition of this article was released in September 2023.

Leave a Reply