Over 72 million years ago, the western seas of the Pacific Ocean harbored one of the most formidable ocean predators in history.

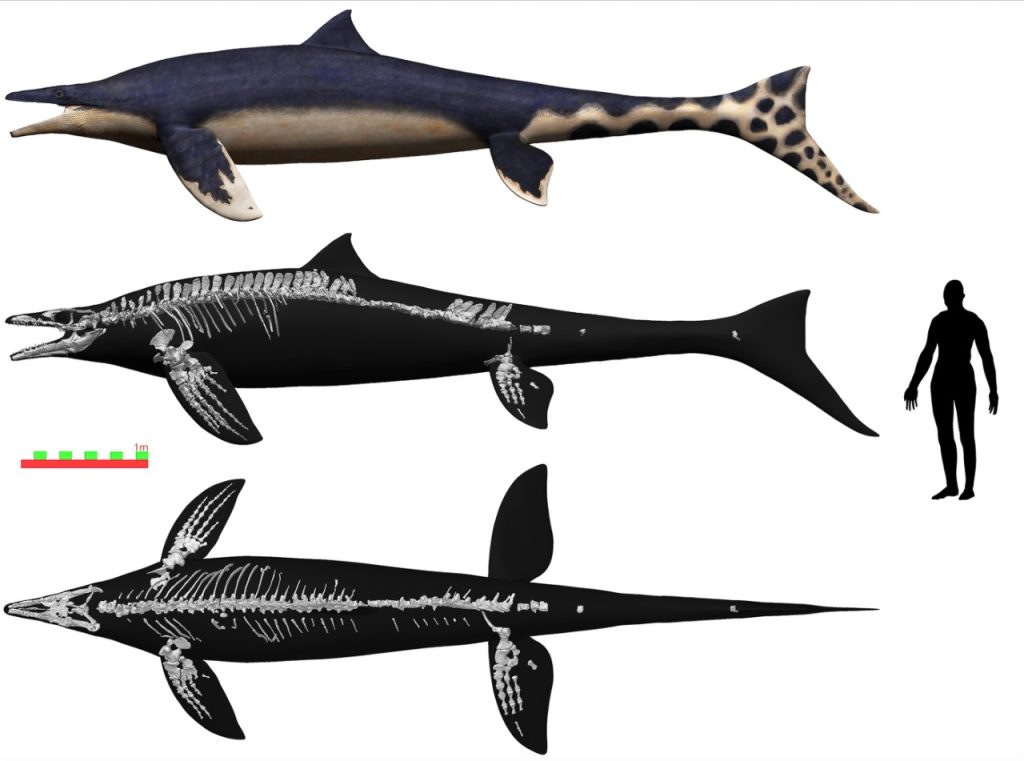

Comparable in size to a bus, this colossal air-breathing creature defied categorization as a mammal, despite its warm-blooded nature. It also differed from crocodiles, despite its similarly shaped head. Belonging to the group of now-extinct marine lizards, it possessed binocular vision, four massive paddle-shaped limbs, a long and powerful tail functioning as a rudder, and possibly a dorsal fin.

Referred to as the Wakayama ‘blue dragon’ by Japanese scientists, this awe-inspiring creature derives its name from both the location of its discovery and the mythical beings of Japanese folklore.

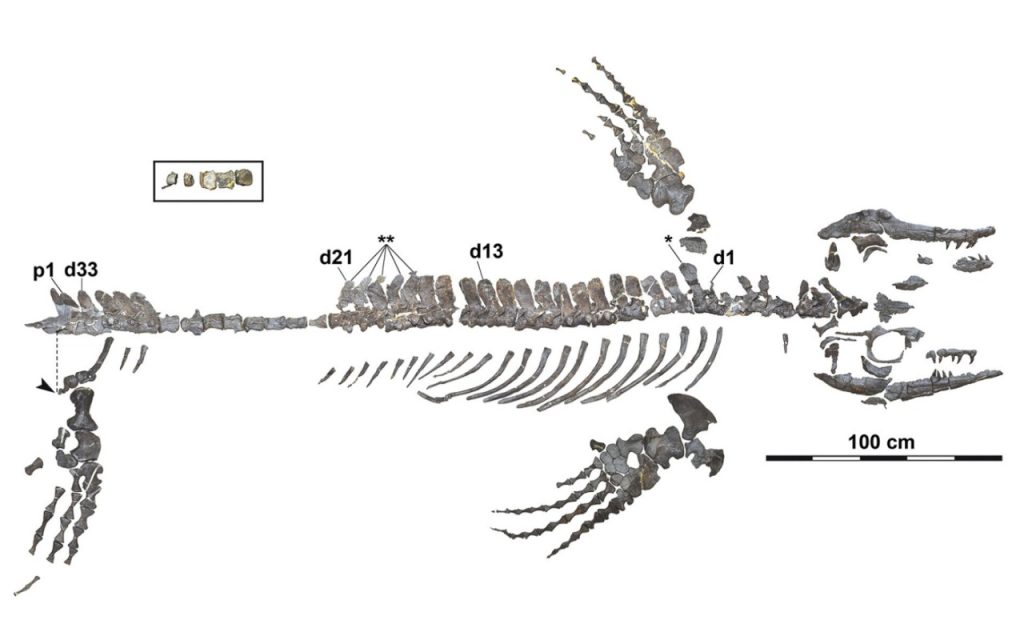

In 2006, along the Aridagawa River in Wakayama, paleontologist Akihiro Misaki from the Kitakyushu Museum of Natural History and Human History unearthed a nearly complete skeleton of an extinct animal. Five meticulous years of effort were invested to delicately extract the bones from the encasing stone.

The formal classification of this 6-meter-long creature reveals a new species of mosasaur: Megapterygius wakayamaensis.

Deciphering the swimming and hunting mechanisms of this ancient giant poses a formidable challenge. According to paleontologist Takuya Konishi from the University of Cincinnati, “We lack any modern analog that has this kind of body morphology – from fish to penguins to sea turtles. None has four large flippers they use in conjunction with a tail fin.”

Mosasaurs, some of the most formidable predators in history, reached lengths of up to 17 meters. Dominating the oceans for approximately 20 million years, these marine lizards were the last of their kind.

Known for their powerful jaws and sharp teeth capable of conquering various prey, including shellfish, turtles, and even other mosasaurs, they were apex predators.

Despite Takuya Konishi’s expertise in mosasaurs, the Wakayama blue dragon presented a unique challenge. Its paddle-shaped flippers, particularly the back ones, stand out for their unusual length compared to mosasaur fossils found elsewhere globally, such as in New Zealand, California, and Morocco.

Distinctive features include spines on its vertebrae that resemble those of dolphins or porpoises, setting it apart from other mosasaurs.

Cetaceans, such as dolphins and porpoises, sport dorsal fins just behind their center of gravity, offering added stability during swimming.

While speculative, scientists studying <em>M. wakayamaensis</em> hypothesizes that this mosasaur may have also possessed a dorsal fin.

Drawing parallels with cetaceans, the Japanese research team suggests that the Wakayama blue dragon could have utilized its front fins for maneuvering, similar to how cetaceans with elongated flippers navigate while swimming.

Distinct from modern cetaceans, the back fins of M. wakayamaensis might have played a role in diving or surfacing, with the main propulsive force coming from its tail.

Contrasting with plesiosaurs, ancient swimming reptiles contemporary to mosasaurs, which relied on their flippers for thrust, the swimming dynamics of mosasaurs pose a unique puzzle.

Scientists, as explained by Konishi, are confronted with questions about the utilization of all five hydrodynamic surfaces—how each contributed to steering or propulsion, challenging our understanding of mosasaur swimming.

The findings are detailed in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.