In humans, briefly drifting into sleep for a few seconds signals inadequate rest, posing potential risks in certain scenarios like operating a vehicle.

However, a recent Thursday-published study reveals that chinstrap penguins engage in numerous short naps throughout the day, accumulating their daily sleep quota of over 11 hours in brief episodes averaging around four seconds each. This unique sleep behavior challenges previous assumptions and sheds light on the sleeping patterns of these fascinating birds.

The authors of the paper in the Science suggest that these non-flying birds may have developed this characteristic as a necessity to maintain constant alertness.

Contrary to earlier assumptions, the study’s outcomes, as argued by the researchers, indicate that the advantages of sleep may accumulate gradually in certain species.

Chinstrap penguins (Pygoscelis antarcticus), recognized for the slender black band of feathers spanning from ear to ear, could possibly be the most prevalent penguin species.

The present estimated population of nearly eight million breeding pairs of chinstrap penguins is predominantly located on the Antarctic Peninsula and islands in the South Atlantic Ocean.

During the nesting period, lone parent penguins must vigilantly protect their eggs from predatory birds known as skuas, particularly when their partners are away on multi-day foraging expeditions.

Additionally, these penguins must safeguard their nests against potential theft of nesting material by other penguins. When a penguin partner eventually returns, the couple undergoes a role reversal.

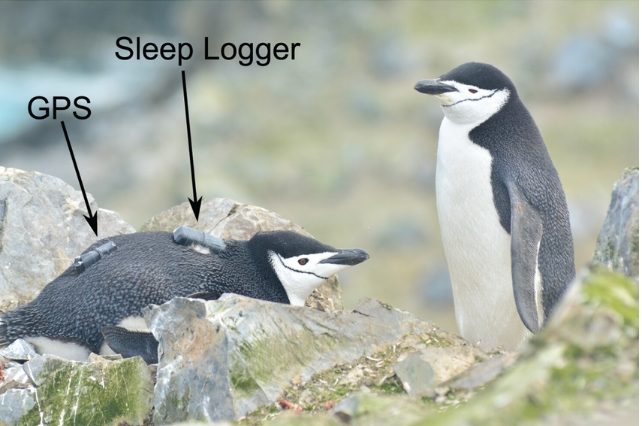

Led by Paul-Antoine Libourel from Lyon Neuroscience Research Centre, a research team implanted electrodes on 14 birds in a colony on King George Island in December 2019. They documented electrical activity in the brain and neck muscles, employing accelerometers and GPS to analyze body movement and location.

Coupled with video documentation and continuous observation spanning several days, researchers successfully identified numerous distinctive behaviors.

The penguins exhibited their sleep patterns while either standing or lying down to incubate their eggs, with an average sleep episode lasting 3.91 seconds. Collectively, they engaged in more than 10,000 sleep bouts each day.

Notably, penguins situated on the outskirts experienced more extended and deeper sleep episodes compared to those positioned in the colony’s center. This phenomenon can be attributed to heightened disturbances, noise, and potential nest material theft risks prevalent in the central areas.

While the scientists didn’t directly assess whether the birds were reaping the rejuvenating advantages of sleep, the penguins’ successful breeding endeavors strongly suggested that this was likely the case. The intervals of neuronal quietness were considered opportunities for rest and recovery.

Conversely, in humans, sleep-disrupting conditions like sleep apnea can adversely affect cognitive function and potentially trigger neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

In a corresponding commentary, researchers Christian Harding and Vladyslav Vyazovskiy expressed their views that “Thus, what is abnormal in humans could be perfectly normal in birds or other animals, at least under certain conditions,”