Centuries before communities in Central Eurasia adopted agriculture, subarctic hunter-gatherer groups were constructing some of the earliest permanent fortified settlements, challenging the traditional belief that settled societies depended on farming.

Recent research suggests the identification of the oldest fortifications in the frigid north, if not globally, near a bend in the Amnya River in Western Siberia.

The Amnya archaeological sites were officially discovered starting in 1987, but recent radiocarbon dating reveals that the main pit house at Amnya Site I, along with its fortifications, dates back around 8,000 years.

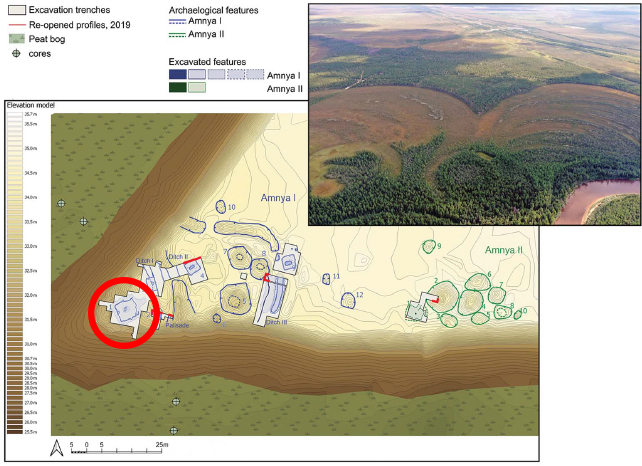

The ancient structure (highlighted in red in the illustration below) now appears as a broad depression in the ground, once safeguarded by a ditch and possibly another pit house. Radiocarbon dating indicates construction in the final century of the seventh millennium BCE.

In the sixth millennium BCE, additional enhancements were made, with the construction of two ditches at the rear of the site. This period saw the establishment of more buildings, embankments, and fences, indicating a phase of more sustained habitation at the site.

Simultaneously, the Amnya II site emerged 50 meters to the east (depicted in green in the diagram above).

As per an international team of archaeologists, spearheaded by researchers at the Free University of Berlin, both sites challenge the conventional understanding of the capabilities of hunter-gatherer groups.

It’s evident that in the Stone Age, it wasn’t only farming communities that constructed permanent, fortified settlements.

Archaeologist Tanja Schreiber from the Institute of Prehistoric Archaeology in Berlin highlights, “Our new palaeobotanical and stratigraphical examinations reveal that inhabitants of Western Siberia led a sophisticated lifestyle based on the abundant resources of the taiga environment,” says.

The West Siberian taiga, a sometimes swampy, coniferous forest habitat in the subarctic region, hosted herds of elk and reindeer around 6,000 BCE. The river teemed with fish, including pike and salmonids.

In such fertile areas, even mobile foraging groups had a compelling reason to safeguard their resources against opportunistic raiders or hungry neighbors.

While the exact purpose of the Amnya fortifications remains unclear, researchers speculate that the site may have stored surplus food, possibly fish oil, fish, and meat, prepared through smoking and preservation.

“They don’t have to grow or raise resources,” Piezonka told Science Magazine’s Andrew Curry. “The surrounding environment provides them seasonally. It’s like harvesting nature.”

The intricately decorated pottery remnants discovered at the site are believed to be containers used for storing the food.

It’s uncertain whether the structures at the Amnya sites were inhabited or defended throughout the year. Nevertheless, it appears to have been a seasonal settlement for a hunter-gatherer group in western Siberia, at least during certain times of the year.

While several Stone Age forts have been discovered in this region, none match the age of the Amnya I site. In Europe, similar sites only appear centuries later, emerging after the advent of agriculture.

“The construction of fortifications by forager groups has been observed sporadically elsewhere around the world in various – mainly coastal – regions from later prehistory onwards, but the very early onset of this phenomenon in inland western Siberia is unparalleled,” writes the international team of archaeologists.

Traditionally, archaeologists have assumed that foraging communities were not yet societally or politically ‘complex’ enough to build monumental, permanent structures that needed to be maintained or defended.

Yet ongoing research at the Amnya promontory and other archaeological sites around the world suggests that cultivating crops and rearing animals aren’t the only incentives for such activity.

Göbekli Tepe, for instance, is a massive stone assembly in present-day Turkey constructed around 11,000 years ago. It was built before the advent of agriculture and is considered to be the oldest known megalith in the world. It seems hunter-gatherers gathered at this site to bid farewell to their dead or to stage sacred ceremonies.

Similarly, at the Amnya site in Siberia, archaeologists have found ‘<em>kholmy</em>’ mounds, which are described as “large-scale ritual structures in the landscape”.

Researchers suspect that a shift in climate roughly 8,000 years ago created the stage for an abundance of seasonal resources in western Siberia, prompting an influx of human migrants.

The development of fishing and hunting strategies, or the advancement of food storage may have then led to a surplus of food, which needed to be defended.

It’s also possible that the crowding of various hunter-gatherer groups in one region promoted a culture of raiding.

“Management of these surpluses then led to changes in the socio-political structuring of populations and the emergence not only of wealth inequality and exclusive property rights, but also of increased community cohesion, for example through collective work on, and use of, monumental constructions,” suggest the researchers.

More work at the Amnya site is currently underway, and archaeologists are making sure to keep their minds open. The traditional notion of a hunter-gatherer that persists in many academic texts may soon need some serious revision.

The study was published in Antiquity.