Elevated cholesterol levels are increasingly prevalent, impacting nearly 2 in 5 adults in the United States. A groundbreaking vaccine in the works offers a potential and cost-effective solution to reduce levels of ‘bad’ cholesterol in the body.

This harmful cholesterol, in the form of low-density lipoproteins or LDLs, poses a risk of creating hazardous blockages in the arteries, diminishing oxygen flow to the heart, or triggering blood clots that may result in a stroke.

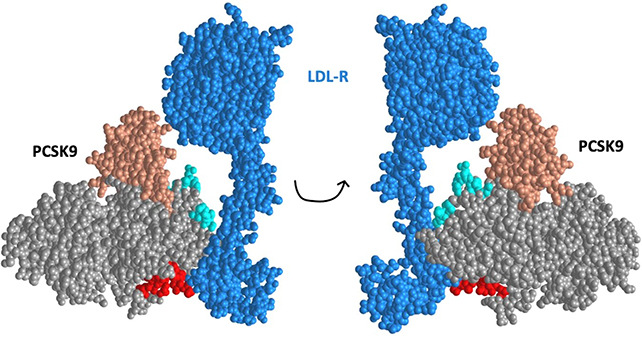

In experiments conducted on mice and monkeys, a team led by researchers from the University of New Mexico and the University of California, Davis successfully lowered LDL levels by targeting a protein known as proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), which has a significant connection to LDLs.

“The vaccine is based on a non-infectious virus particle,” says molecular geneticist Bryce Chackerian from the University of New Mexico.

“It is just the shell of a virus, and it turns out that we can use that shell of a virus to develop vaccines against all sorts of different things.”

The liver cells host special receptors crucial for maintaining LDLs at a safe level. However, an overabundance of PCSK9 can compromise these receptors, diminishing their effectiveness. Consequently, more harmful cholesterol circulates in the bloodstream, posing health risks.

Factors such as genetics and diet play a role in the production of PCSK9 in the body. In this context, the integration of small fragments of PCSK9 with the non-infectious virus particle induced an immune system response. This response effectively targeted and neutralized the PCSK9 protein.

The vaccine crafted by the researchers demonstrated the capability to lower bad cholesterol by as much as 30 percent. While being equally effective as current PCSK9 inhibitors, it presents a potential solution that could be more cost-effective.

“We are interested in trying to develop another approach that would be less expensive and more broadly applicable, not just in the United States, but also in places that don’t have the resources to afford these very, very expensive therapies,” says Chackerian.

We’re still a considerable distance away from having a vaccine ready for human use, but these results are promising. The solution could be more budget-friendly than current alternatives and offer protection for about a year per dose.

With a decade of development already behind it, the next step for the vaccine involves human trials, necessitating additional study and funding. This effort is essential, considering its potential to mitigate the approximately 18 million lives lost globally every year to cardiovascular disease.

“We hope to have a vaccine in people in the next 10 years,” says Chackerian.

The findings have been published in NPJ Vaccines.