Fed up with enduring abdominal cramps for over a week, a 37-year-old woman from the French island of Réunion, east of Madagascar, sought relief at a hospital emergency department, only to uncover that she was, indeed, pregnant.

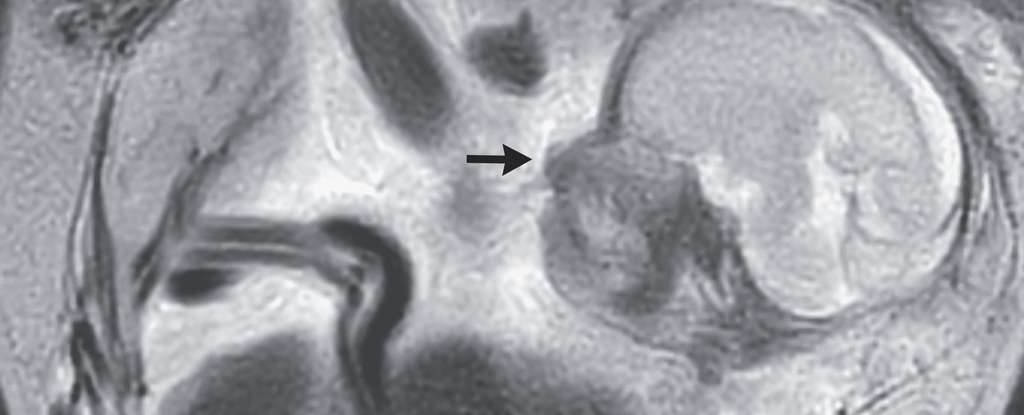

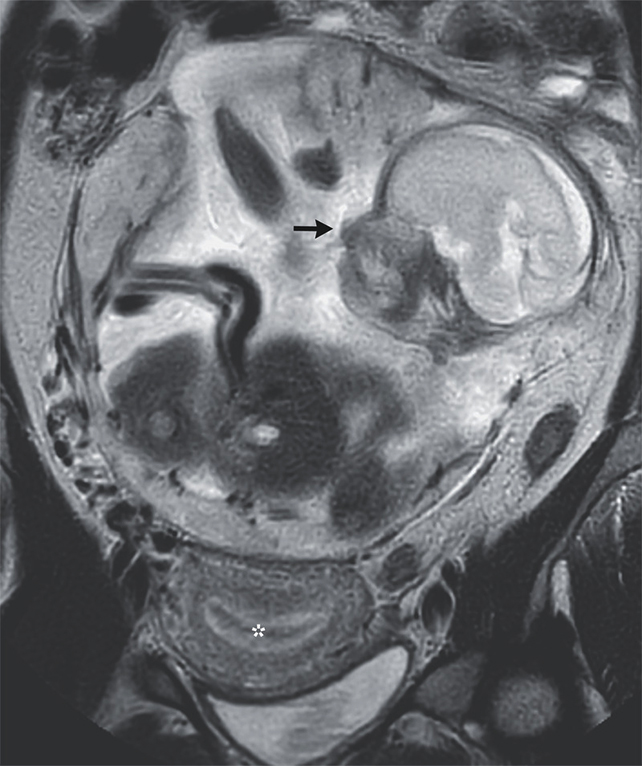

Subsequent scans unveiled an unexpected revelation. Despite a 23-week-old baby joyfully kicking inside the woman’s body, her uterus appeared entirely vacant. Instead, the fetus had securely attached itself to the membrane lining the abdominal cavity, just above the mother’s tailbone.

Recognizing the scenario as a situation of abdominal ectopic pregnancy, the woman’s medical team redirected her to a more suitable hospital. At 29 weeks, the baby was delivered through surgery and placed into neonatal intensive care. Approximately two months after birth, the child received medical clearance to go home.

The uterus is an intricately designed wonder of biology, evolved to safeguard and nurture a fertilized egg until the fetus reaches the strength to withstand the external environment.

In approximately one in every hundred pregnancies, the fertilized egg takes an entirely different path, choosing to bypass the womb’s nurturing environment and instead embedding itself into less conducive tissue for its development.

Most ectopic pregnancies attach themselves to the lining of one of the two fallopian tubes that transport ova from the ovaries, leading to a potentially life-threatening situation if the embryo continues to grow. Without appropriate medical intervention, up to 10 percent of such pregnancies may result in the loss of both the parent’s and the child’s lives.

However, in fewer than one percent of ectopic pregnancies, the newly developed embryo moves out of the internal environment of the uterus and into the abdominal cavity. There, it finds a place against the peritoneal membrane, spleen, or another tissue or organ, establishing itself and forming a placenta.

Interestingly, this configuration doesn’t always have an immediate negative impact on the embryo. However, over time, the increasing weight of the growing child and the pressure from surrounding organs present risks to both the child’s development and the health of the parent.

Maternal mortality beyond 20 weeks of gestation can occur in nearly one in five cases, leading to shock, hemorrhaging, and multiple organ failure, as outlined in this study.

For the woman in this case, a prompt visit to the emergency department likely saved her life. An ultrasound and MRI revealed that while her uterus’s lining was fully prepared to support a growing embryo, there was no embryo present.

Although the placenta’s arteries were blocked and a portion of the organ was extracted during the surgery to deliver her child, it required a subsequent procedure 12 days later to meticulously remove the remaining tissue.

The precise factors triggering embryos to undergo such rare and unconventional migrations remain unclear. Research on ectopic pregnancies, in general, suggests a history of previous cases could elevate the risk of recurrence, while certain sexually transmitted infections, endometriosis, and pelvic inflammatory disease may also contribute to the phenomenon.

According to a case study, the patient, who has had two full-term vaginal deliveries, one miscarriage, and no prior surgeries or relevant infections, lacks a medical history that might shed light on the reasons behind her unusual pregnancy.

As per the case study, both the mother and the child were in relatively good health upon leaving the tertiary care hospital where the baby was delivered – a rare positive outcome for a severe medical condition that impacts only a small fraction of all pregnancies.

Although the patients were lost to follow-up, we can imagine they both went home with one incredible story to tell.

This case study was featured in the New England Medical Journal.