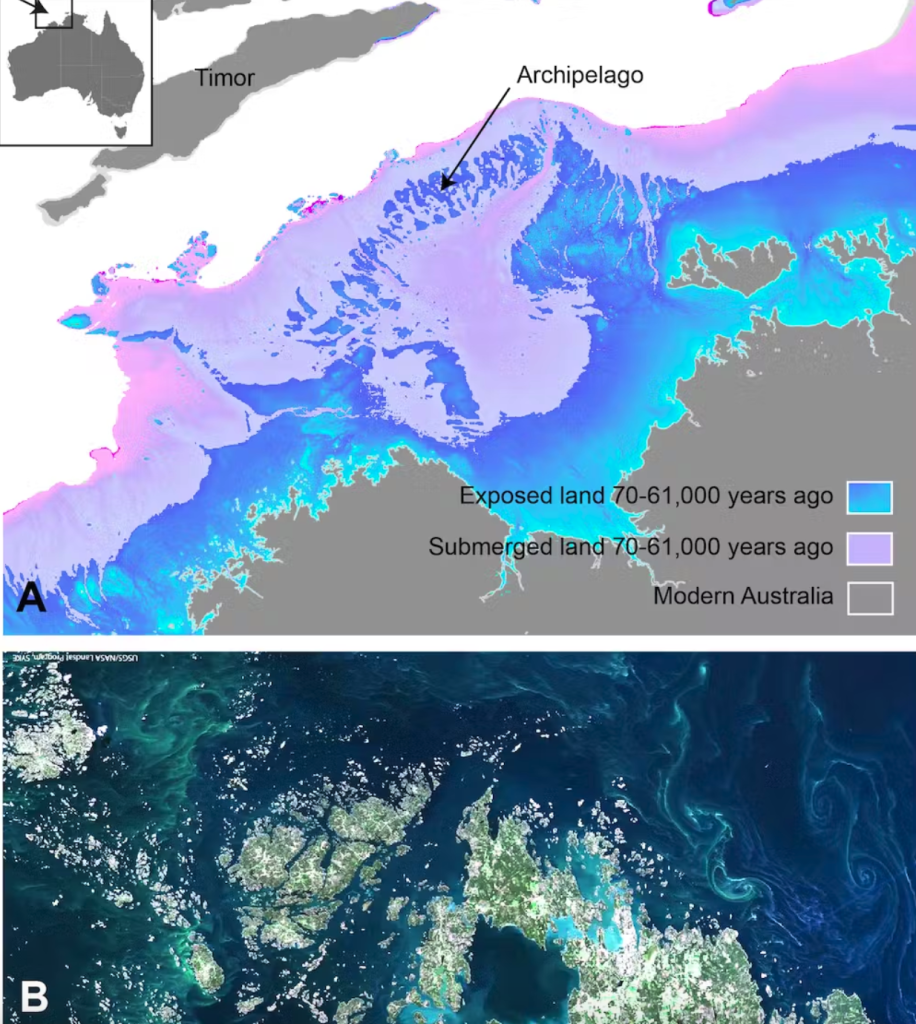

Throughout Australia’s 65,000-year human history, the northwest continental shelf, now submerged, once linked the Kimberley and western Arnhem Land. This extensive and inhabitable region spanned nearly 390,000 square kilometers, surpassing the current size of New Zealand by one-and-a-half times.

It probably formed a unified cultural zone, exhibiting similarities in ground stone-axe technology, rock art styles, and languages observed by archaeologists in both the Kimberley and Arnhem Land.

Abundant archaeological evidence suggests that humans once inhabited continental shelves – areas now submerged – across the globe. Concrete proof has been unearthed from underwater sites in the North Sea, Baltic Sea, and Mediterranean Sea, as well as along the coasts of North and South America, South Africa, and Australia.

In a recently published Quaternary Science Reviews study, we unveil insights into the intricate landscape that once existed on the Northwest Shelf of Australia. This landscape differed significantly from any found on our continent today.

A continental split

Around 18,000 years ago, the conclusion of the last ice age led to warming that triggered a rise in sea levels, submerging extensive areas of the world’s continents. This transformative process separated the supercontinent of Sahul into New Guinea and Australia, and isolated Tasmania from the mainland.

Contrary to other parts of the world, it was commonly believed that the submerged continental shelves of Australia were environmentally unproductive and saw limited use by First Nations peoples.

This evidence comes from sites in the Cave Dig, which demonstrate that ancient Australians embraced a coastal lifestyle. The now-submerged northwest continental shelf, submerged around 18,000 years ago as the last ice age ended and warming led to rising sea levels, is a testament to the rich history of human habitation in Australia.

An ancient Aboriginal archaeological site has been uncovered on the seabed in a groundbreaking discovery. Stone tools found off the coast of the Pilbara region in Western Australia provide a unique glimpse into the ancient history of Indigenous peoples, showcasing their adaptability and resourceful use of the submerged landscape.

Until now, researchers have been limited to speculation regarding the characteristics of the submerged landscapes that ancient populations traversed before the conclusion of the last ice age and the extent of their populations.

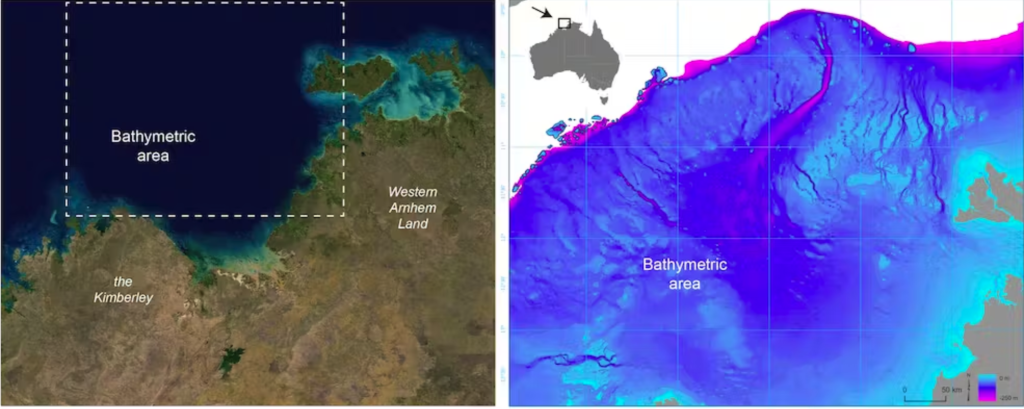

Our recent study of the Northwest Shelf provides additional insights, revealing the presence of archipelagos, lakes, rivers, and a vast inland sea in this region.

Mapping an ancient landscape

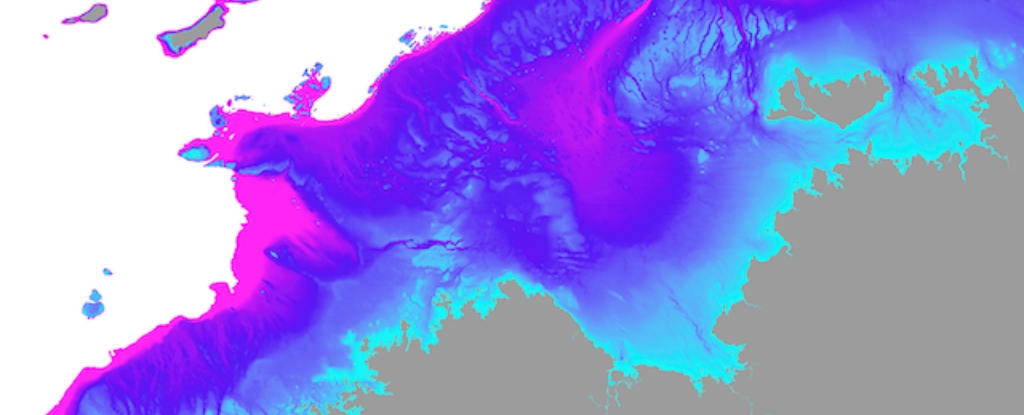

To understand the transformations in the landscapes of the Northwest Shelf over the last 65,000 years of human history, we utilized detailed maps of the ocean floor, projecting historical sea levels onto them.

During periods of low sea levels, an expansive archipelago of islands emerged on the Northwest Shelf of Sahul, stretching approximately 500km towards the Indonesian island of Timor. This archipelago formed between 70,000 and 61,000 years ago, remaining stable for about 9,000 years.

These islands’ diverse ecosystems could have facilitated a gradual migration from Indonesia to Australia, with the archipelago serving as stepping stones for human movement.

As the world entered the last ice age, polar ice caps expanded, leading to a significant drop in sea levels, fully exposing the shelf for the first time in 100,000 years.

This area featured a diverse mix of livable freshwater and saltwater environments, with the prominent Malita inland sea being the most notable among them.

Our projections indicate its existence for a span of 10,000 years, from 27,000 to 17,000 years ago, encompassing a surface area exceeding 18,000 square kilometers. A contemporary comparison can be drawn to the Sea of Marmara in Turkey.

Our research reveals that during the last ice age, the Northwest Shelf harbored a substantial lake located just 30km north of the contemporary Kimberley coastline. At its peak, it would have been half the size of Kati Thandi (Lake Eyre). The ocean floor maps still display remnants of ancient river channels that once fed into the Malita Sea and the lake.

A thriving population

An earlier research indicated that the population of Sahul might have expanded to millions of individuals.

Ecological modeling suggests that the submerged Northwest Shelf, now beneath the ocean, could have sustained a population ranging from 50,000 to 500,000 people at different points over the past 65,000 years. The population would have reached its peak around 20,000 years ago during the height of the last ice age when the entire shelf was above water.

New genetic research, drawing data from individuals residing in the Tiwi Islands just east of the Northwest Shelf, supports the notion of substantial populations around 20,000 years ago. This research contributes to the understanding of the large populations that could have inhabited the region during the height of the last ice age.

As the last ice age concluded, the escalating sea levels submerged the shelf, prompting communities to retreat as waters engulfed formerly productive landscapes.

As populations retreated, the diminishing available land forced communities to come together. During this period, new styles of rock art emerged in both the Kimberley and Arnhem Land.

The rise in sea levels and the submergence of the landscape are also documented in the oral histories of First Nations people from various coastal regions, believed to have been passed down for over 10,000 years.

This recent revelation of the intricate and complex ways in which First Nations people responded to rapidly changing climates adds further weight to the call for more Indigenous-led environmental management in this country and beyond.

As we navigate an uncertain future together, the profound Indigenous knowledge and experience rooted in deep time will be crucial for successful adaptation.

This article has been reissued from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.