A puzzling ancient burial ground, baffling Finnish archaeologists for decades, may be among the largest Stone Age cemeteries in northern Europe, suggests a recent study.

Situated on the fringes of the Arctic Circle in Tainiaro, known for its prolonged and harsh winters, the site was initially discovered in 1959. Despite subsequent studies in the late 1980s, the findings from these excavations remained undisclosed.

While thousands of artifacts were documented, the sandy soils were found to contain ash and display streaks of red ochre. Curiously, no human remains have ever been unearthed in the numerous shallow pits at Tainiaro, leaving researchers pondering the purpose of gatherings along the forested shores of an almost-Arctic estuary.

In a recent analysis led by archaeologist Aki Hakonen from the University of Oulu in Finland, the notion that the site served as a graveyard gains strength. The study suggests the existence of up to 200 potential burial pits, crafted some 6,500 years ago by Stone Age communities recognized for their nomadic forager lifestyle.

“Even though no skeletal material has survived at Tainiaro,” Hakonen and colleagues write in their paper, “Tainiaro should, in our opinion, be considered to be a cemetery site.”

To arrive at this conclusion, the research team delved into the historical records of the site, meticulously relocating previously excavated trenches. They then conducted additional excavations, comparing the shape, size, and contents of the pits to other Stone Age burial sites across Finland.

Despite the potential decay of bones in the region’s acidic soils over thousands of years, the site yielded thousands of preserved stone artifacts, remnants of pottery, and a few charred animal bones, scattered throughout the area.

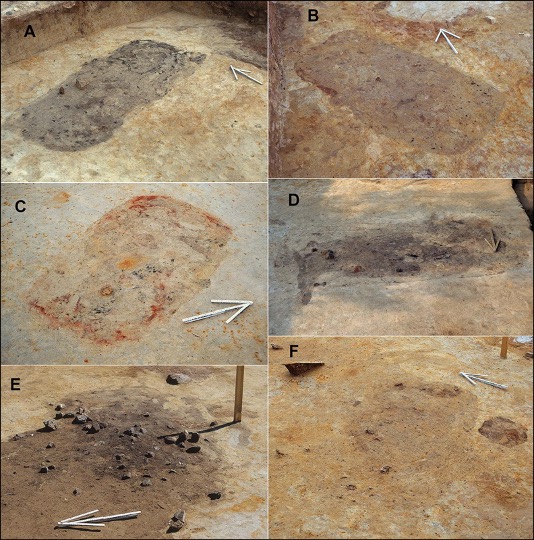

The majority of the pits revealed traces of ash and charcoal, though not reaching the extent found in thick layers of burnt material unearthed at Stone Age hearths in other locations. Some pits displayed intermittent streaks of red ochre, but these were insufficient to categorize the depressions as ceremonial burial plots.

Nevertheless, the shape and size of the Tainiaro pit closely mirrored those of hundreds of Stone Age graves discovered at 14 cemeteries across northern Europe. Many Tainiaro pits took the form of shallow rectangles with rounded corners, measuring between 1.5 and 2 meters in length and approximately half a meter in depth.

After conducting their analysis, the team identified 44 out of an estimated 200 pits as potential graves. However, it’s important to note that only one-fifth of the site has been excavated thus far, indicating that further studies could unveil more insights.

If, indeed, the pits turn out to be graves numbering in the hundreds, it suggests that Stone Age societies residing near the Arctic may have been more substantial than previously believed. In comparison, other gravesites in the vicinity are notably smaller, with Hakonen mentioning approximately 20 burial pits.

In the previous year, researchers made a significant discovery, unearthing the elaborate grave of a child in contemporary Finland. The intricately adorned grave, adorned with layers of feathers and fur, provided valuable insights into the Stone Age communities in the area, hinting at a profound connection with death.

Nevertheless, Tainiaro may not have served solely as a burial ground, considering the diverse array of tools and charred materials uncovered at the site, as highlighted by Hakonen and colleagues. Nomadic communities might have engaged in activities such as lighting fires or crafting stone tools in proximity to the graves, creating a dynamic coexistence with the deceased, if only for a period.

“Many questions about Tainiaro remain unanswered,” the team writes.

“For the time being, however, the notion that a large cemetery seems to have existed near the Arctic Circle should cause us to reconsider our impressions of the north and its peripheral place in world prehistory.”

The study has been published in Antiquity.

The researchers have outlined plans to employ ground-penetrating radar for a non-invasive study of the site. Hakonen suggests that analyzing soil samples could provide valuable information, including human DNA, fossilized hair, or remnants of animal furs and bird feathers. These analyses aim to enhance our understanding of potential burial practices employed at the site.