In the savannahs and rainforests of tropical Africa, a bond formed with an ape lasts a lifetime.

A research project involving 26 captive chimpanzees and bonobos, conducted by evolutionary biologist Laura S. Lewis from Harvard University (who was a student at Stanford University during the study), reveals that non-human apes possess the ability to recognize family members and friends even after decades of separation.

At the Kumamoto Sanctuary in Japan, a 46-year-old bonobo named Louise demonstrated the remarkable ability to recognize two fellow bonobos she hadn’t encountered since 1995 – an impressive reunion occurring 26 years later.

This marks the lengthiest recorded social memory observed in any non-human animal. These findings might offer insights into the evolution of our ability to remember faces, a skill allowing us to recognize thousands of individuals over decades, as discussed in a related study.

The research was carried out at multiple institutions globally, encompassing the Kumamoto Sanctuary, Edinburgh Zoo in Scotland, and the Planckendael Zoo in Belgium.

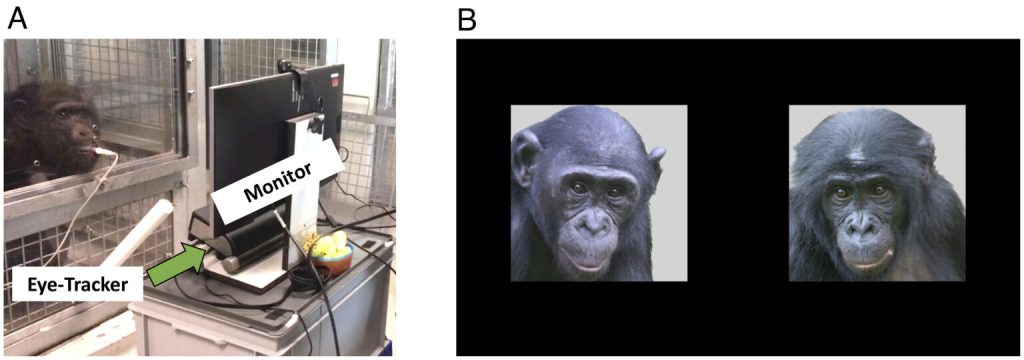

Every chimpanzee or bonobo involved in the research was introduced to a computer, and this device was utilized to present two photos side by side to the ape as they enjoyed a refreshing sip of juice.

While sipping on juice, each participant was presented with two photos on the computer screen – one featuring an unfamiliar face and the other showcasing the countenance of a past companion, relative, or adversary with whom the ape had coexisted for a minimum of one year.

During a brief three-second window of observing the photos, an eye-tracking tool meticulously monitored the participant’s visual focus.

“It was a really simple test: Do they look longer at their previous groupmate, or are they looking longer at the stranger?” explains Lewis.

“And we found that, yes, they are looking significantly longer at the pictures of their previous groupmates.”

As our nearest living relatives, it’s not astonishing that chimpanzees and bonobos are naturally attracted to faces they’ve encountered previously. Primatologists such as Lewis have observed that these apes exhibit recognition of their human caretakers even after extended periods of separation.

Throughout history, the scientific community has often overlooked the social lives and memories of other animals.

Thanks to the inquisitiveness of researchers like Lewis, a gradual shift is occurring in how we perceive this.

In 2013, a study revealed that dolphins can identify the distinctive whistles of their relatives even after two decades of separation.

Earlier this year, research uncovered that elephant mothers and daughters retain the ability to recognize each other’s scent even after being apart for up to 12 years.

The recent investigation into chimps and bonobos reinforces the notion that we and our ape counterparts possess comparable facial processing mechanisms, crucial for establishing enduring and possibly lifelong connections.

“We don’t know exactly what that representation looks like, but we know that it lasts for years,” says Lewis.

“This study is showing us not how different we are from other apes, but how similar we are to them and how similar they are to us.”

Lewis and her team observed that apes paid greater attention to the familiar faces of longtime friends with whom they had stronger bonds compared to those with whom their connections were less intimate.

This implies that the development of long-term facial recognition may have evolved more as a mechanism for cooperation rather than competition, although additional research is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The length of time spent apart did not appear to affect the outcomes.

“Although more data are needed to determine whether great ape memory lasts beyond 26 years,” Lewis and her colleagues write, “these results indicate that, for at least some nonhuman great apes, the longevity of social memory may be relatively similar to that of humans, which begins to decline after ~15 [years] but can persist 48 years beyond separation”.

If Lewis and her team’s hypothesis is correct, the enduring memory of faces may extend back to our shared ancestor with apes, a period exceeding 6 million years ago.

The research findings have been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.