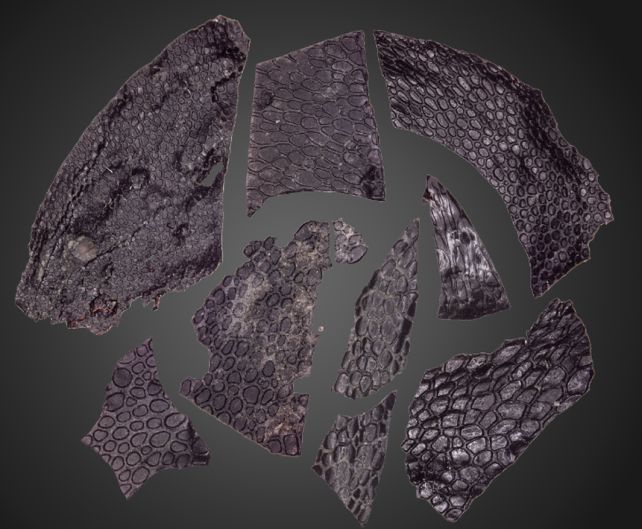

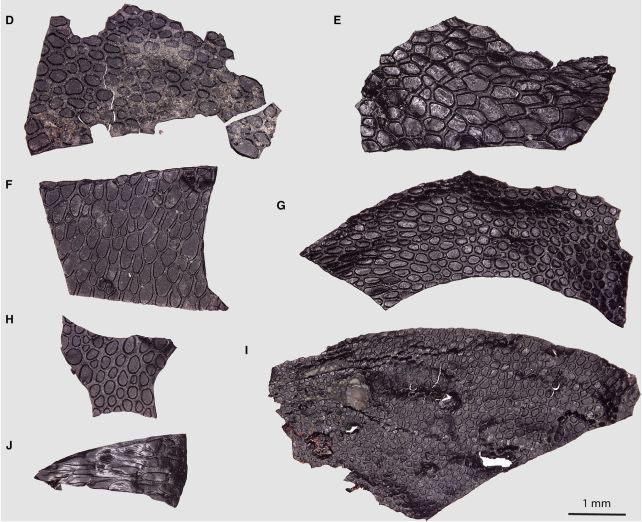

Although minuscule, smaller than a fingernail, a rock unearthed from a deep limestone cave in Oklahoma is expanding our insights into ancient skin.

Paleontologists have identified the preserved texture as the earliest-known instance of fossilized skin among amniotes, a diverse group of animals.

Dating back 290 million years, surpassing the previous record by 21 million years, the wearer of this fossilized skin seems to have been a reptile. The texture resembles the pebbly surface found on the skin of contemporary crocodilians.

Considering the crucial role of skin as a protective barrier, safeguarding against external contaminants, and securing our internal structures, scientists emphasize the significance of this discovery in unraveling the evolutionary history of skin.

Every now and then we get an exceptional opportunity to glimpse back into deep time,

says paleontologist Ethan Mooney of the University of Toronto, who led the research. These types of discoveries can really enrich our understanding and perception of these pioneering animals.

While the fossil record boasts richness and diversity, certain body parts are preserved far less frequently. Soft tissues, such as skin, organs, and connective material, tend to degrade more easily than bones. Often, they vanish before stone can adequately preserve their structure.

Some environments prove ideal for the conservation of soft tissue, and the infilled cave system of Richards Spur in Oklahoma is a prime example. The sediment in this location is exceptionally soft and fine, while the absence of oxygen serves to delay the decay of soft tissues. Moreover, during the Permian period, the cave functioned as an active oil seep, with the hydrocarbons from petroleum and tar permeating the sediment, aiding in the preservation of tissues.

The location is renowned for hosting a varied and abundant collection of early tetrapods. Among the Richards Spur caves, discoveries include some of the earliest-known amniotes—a category of terrestrial vertebrates encompassing reptiles, mammals, and birds.

The recently uncovered skin fossil is truly exceptional. It has been carbonized in 3D, marking the first recorded instance from the Paleozoic era. Additionally, it stands as the earliest-known preserved skin fossil, encompassing not only the outer layer but also structures that are highly likely associated with the deeper dermis layer.

We were totally shocked by what we saw because it’s completely unlike anything we would have expected,

says Mooney.

Finding such an old skin fossil is an exceptional opportunity to peer into the past and see what the skin of some of these earliest animals may have looked like.

Unfortunately, details about the creature to which the skin belonged remain elusive, as no associated skeleton was uncovered. Nonetheless, the distinctive non-overlapping pebbled surface bears a resemblance to the skin of contemporary crocodilians. Additionally, the articulated regions between the scales exhibit similarities to the skin patterns observed in animals like snakes and worm lizards.

According to the researchers, the finding indicates that even in the early stages of amniote divergence, skin was already present and played a significant role.

“In particular,” they write in their paper, the presence of an epidermis with hinges and scale-like protuberances underscores the importance of this component of the amniote skin as a barrier against the harsh terrestrial environment.

Furthermore, the preserved skin provides a novel tool for interpreting the subsequent evolution and emergence of mammalian hair follicles and avian feathers. The first appearance of mammals in the fossil record dates back to approximately 225 million years ago, while birds emerged around 150 million years ago. Consequently, this enigmatic animal could offer valuable insights into the development of our own soft and fleshy skins.

Significant gaps persist in our understanding of how the distinct traits of various animal groups diverged and evolved. Uncovering early instances of these traits provides a rare and unique glimpse into the history of the diverse and fascinating life forms that inhabit our planet.

The findings from the team’s research have been documented in Current Biology.