There is a notable disparity in the aging process between mammals, including humans, and the comparatively rapid aging observed in numerous species of reptiles and amphibians.

In the realm of biological aging, a distinct contrast is evident, with mammals, including humans, experiencing a more prolonged aging trajectory in comparison to the accelerated aging patterns observed in various reptilian and amphibious species.

In his latest scholarly work, João Pedro de Magalhães, a renowned microbiologist from the University of Birmingham, introduces and explains his groundbreaking “longevity bottleneck” hypothesis in a newly released academic publication.

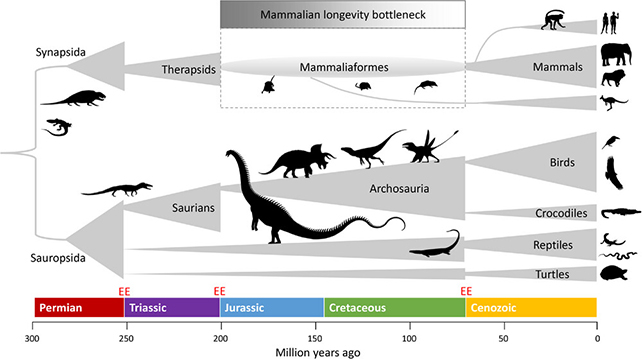

Consider this perspective: during the era of dinosaur dominance on Earth, the survival strategy for significantly smaller mammals necessitated rapid reproduction. This implies that, as the process of evolution unfolded, the genetic traits associated with extended lifespans might have been relinquished in favor of traits supporting quicker reproductive cycles.

de Magalhães says Some of the earliest mammals were forced to live towards the bottom of the food chain, and have likely spent 100 million years during the age of the dinosaurs evolving to survive through rapid reproduction. That long period of evolutionary pressure has, I propose, an impact on the way that we humans age.

The recently published research highlights a noteworthy observation regarding our distant ancestors within the eutherian mammal lineage. It suggests that during the era of dinosaurs, a significant loss occurred in specific enzymes responsible for repairing damage inflicted by ultraviolet (UV) light.

Remarkably, even marsupials and monotremes exhibit a deficiency in at least one of the three enzymes crucial for repairing damage caused by ultraviolet (UV) light, known as photolyases. Whether this deficiency correlates with their comparatively shorter lifespans remains uncertain.

A potential explanation suggests that the decline in these enzymes could be linked to mammals adopting a more nocturnal lifestyle for enhanced safety. Over the course of millions of years, this evolutionary shift might have led to the development of compensatory mechanisms, such as the use of sun cream in contemporary times, to mitigate the impact of reduced UV repair abilities. This scenario serves as an illustration of a mechanism for repair and restoration that might have been otherwise inherent in our biological makeup.

Additional indications also exist. Consider teeth, for instance: specific reptiles, such as alligators, have the capacity to continuously grow teeth throughout their lifetimes. In contrast, humans lack this ability – potentially an outcome of genetic selection stretching back hundreds of thousands of years.

de Magalhães says “We see examples in the animal world of truly remarkable repair and regeneration. That genetic information would have been unnecessary for early mammals that were lucky to not end up as T Rex food.

Certainly, several mammals, such as whales and humans, do achieve centennial milestones in their lifespans. The inquiry into whether we attain such longevity while adhering to the limitations set by our ancestors with shorter lifespans or if we have evolved mechanisms to remain unaffected by those constraints holds promise for future research endeavors.

While just an hypothesis at the moment, there are lots of intriguing angles to take this, including the prospect that cancer is more frequent in mammals than other species due to the rapid aging process,” says de Magalhães.

The research has been published in BioEssays.

Leave a Reply